How natural can the seawater in a large inland aquarium be? New study at Georgia Aquarium gives scientists a good sign

Sea creatures living in captivity need to go to the bathroom, too. That means aquarium water must be cleaned of waste like ammonia, nitrites, and nitrates. Good bacteria break down nitrogen compounds at Georgia Aquarium, and in a new study, some bacterial communities there emulated those found naturally in oceans surprisingly well.

“I didn’t expect this,” said Petit Institute researcher Frank Stewart, principal investigator of a study led by the Georgia Institute of Technology. “The microbial communities are seeded from microbes coming from the animals and their food in an aquarium that does not tap into the ocean. But these looked like natural marine microbial communities.”

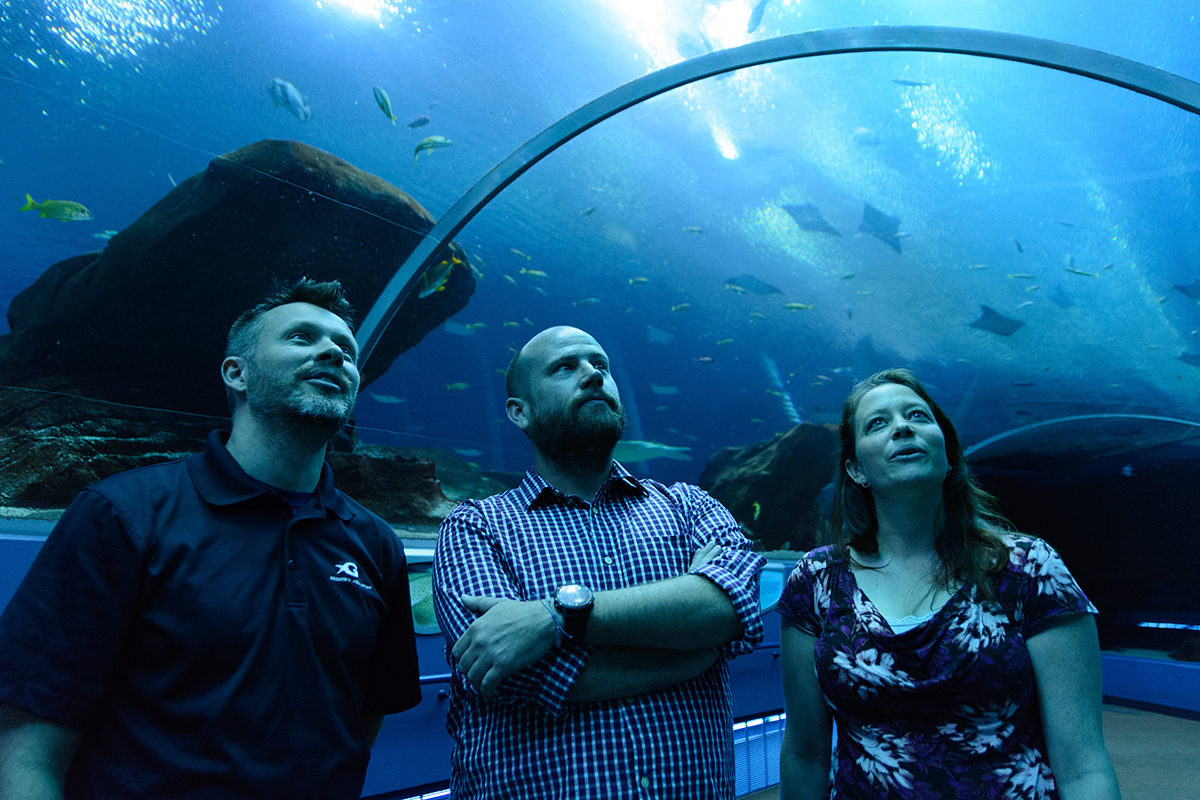

That’s happy news for the thousands of creatures who live in Georgia Aquarium’s Ocean Voyager, the largest indoor oceanic exhibit in the United States. Watch the video and read the story in Georgia Tech’s Research Horizons right here.